MBA. Hellen Ruiz Hidalgo

Strategic Communicator

Foreign Trade Observatory (OCEX)

Vice-Rectory for Research - Distance Learning State University (UNED)

Introduction Without having a precise date of its beginning, at least from the beginning of this century, the international panorama has been in a geopolitical process of transformation. One its main traits is, certainly, the relative lessening of the significance of the great powers that dominated the post-war and the post-Cold War commercial scenario, the emergence of national players with extensive territories and a large population, but that, until recently, they have occupied a space of less relevance.

In 1980, Antoine W. Van Agtmael, an economist working for the World Bank's International Finance Corporation coined the term “emerging” which gave rise to several related concepts such as “emerging markets” or, later, “emerging countries.” The outset of this concept, primarily oriented for financial investment, was, in fact, 10 years ahead of globalization and 20 years before the actual emergence of these countries. At the beginning of this century, Van Agtmael was already talking about “The Century of Emerging Markets”. Many emerging countries seem to have made the decision to enter and to show their presence in the greatest number of international political spaces (Maihold y Villamar, 2016).

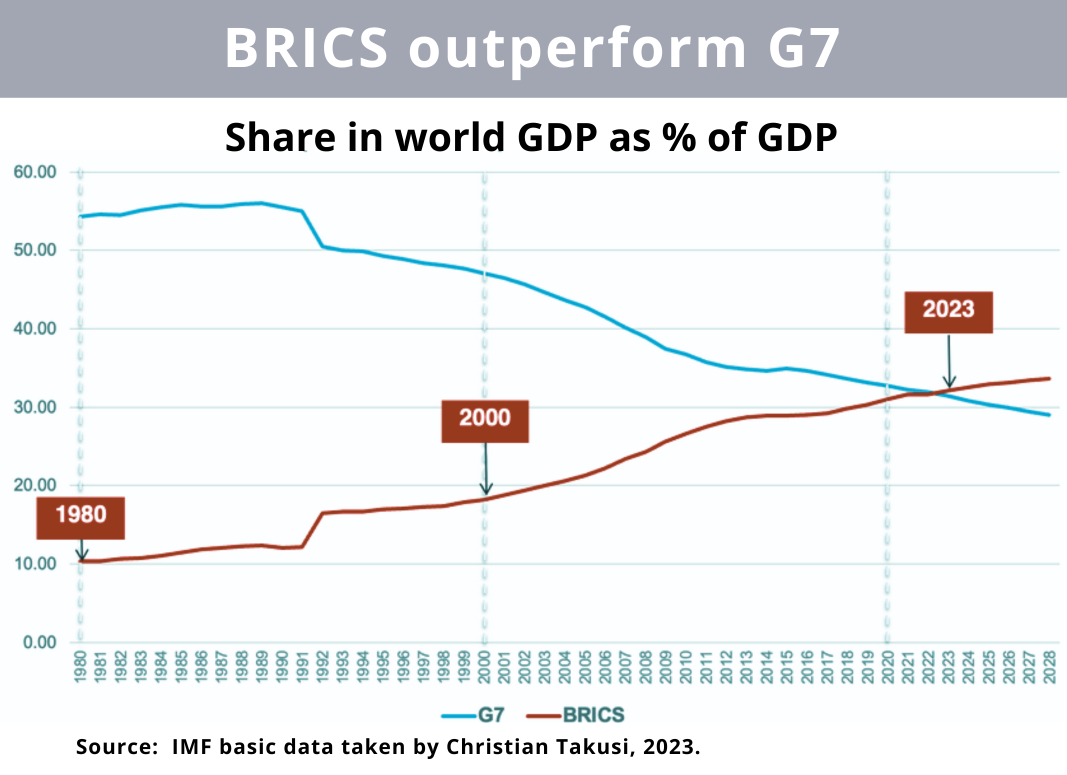

These types of market-countries have been leaving the purely financial or commercial sphere and have entered into processes of geopolitical association with the express objective of participating more strongly in the governance of the world economy (Haibin, Niu, 2012). Its most characteristic associative expression are the countries currently called BRICS+, an associative acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa and several other countries (the “+” refers to the new members of the Middle East and North Africa: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran , Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates). With these new inclusions, the BRICS+ represent already more than 45% of the world's population and their collective GDP (PPP) constitutes currently a larger part of the world's GDP than the G7 countries, 36% vs 30% (Takushi, Christian, 2023).

The BRICS+ countries are flanked by countries considered “developed” and “underdeveloped” and have one or more of certain distinctive characteristics in common (Salama, Pierre. 2014):

- Extensive territory. with abundance of natural and extractive resources;

- High population volume, combined with high levels of poverty and low per-capita income;

- Economic openness to trade and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) that seeks efficiency;

- Growth potential of its internal consumption;

- Higher annual economic growth rate than the average of developed countries.

- Monetary vulnerability, dependent on the need to defend the competitiveness of its exports, even with monetary manipulation of its exchange rate.

- Reduced middle class, which slows down technological development, creates inequalities in the distribution of wealth, which in reality induces high political instability.

This capsule seeks to offer panoramic information about the BRICS+, but not in its economic or commercial aspects, but in its aspiration for active and decision-making participation in the governance of the world economy. From this angle, the BRICS+ will be approached within the context of a change of era marked, among other things, by changes in the relative weight of the countries that rule global geopolitical governance. That regency has been dominated, since 1975, by the G7 countries, under American leadership. The BRICS+ manifest themselves as a challenge to the G7's control of the multilateral organizations that govern the world economy. The BRICS+ propose a movement towards multilateralism without hegemonies.

That is why this capsule begins discerning the formation of global governance, based on the Bretton Woods Agreements, as background to the presentation of the BRICS+.

Background 2001 – The economic anachronism of the G7: Bretton Woods

Between July 1 and 22, 1944, within the framework of the newly founded United Nations, an international economic and financial conference was convened in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States. Its aim was to create a stable global economic and financial system. The result of that conference were the so-called “Bretton Woods Agreements”, in which the main economic, commercial and financial institutions that oversee the world economy were created: the GATT, World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (Marín Sánchez, 2011). Its purpose was to establish a stable multilateral economic and financial system that would oversee all countries in the post-war period. In this way, it has been possible to ensure free trade, promote economic growth, prevent financial crises and protect countries from the protectionism that conditioned, in part, the outbreak of the two great world wars. One of the premises of the functioning of these institutions and the international economy was the creation of the North American dollar standard. This system forced the countries of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to maintain a fixed exchange rate with respect to the dollar, the US central bank to back its currency with gold and to deliver from its gold reserves, one ounce for every $35 dollars they would like to convert.

The Breakup of the Dollar-Standard. In the 70s of the previous century, a global financial crisis occurred and the United States could not maintain the same convertibility rate of its currency for gold. As a result, Richard Nixon, then president of the United States, suspended this monetary regime on August 15, 1971 and, since 1973, in the currency markets, countries were allowed to freely float their currencies. From that moment on, national currencies do not have to be anchored to a fixed exchange rate and central banks are not obliged to link their policy to maintaining a specific parity. It is the birth of national monetary policies, themselves. This created a new situation, with a high possibility of volatility that could lead to highly dangerous international conditions (Duque, 2014).

That is, by floating their exchange rate, countries could lower the national costs of their products, thus promoting their exports and inhibiting their imports. It is the management of its competitiveness through the manipulation of its currencies, improving its trade balance and affecting the trade balance of its partners, that could lead, eventually, to new forms of trade wars through manipulation of the foreign exchange.

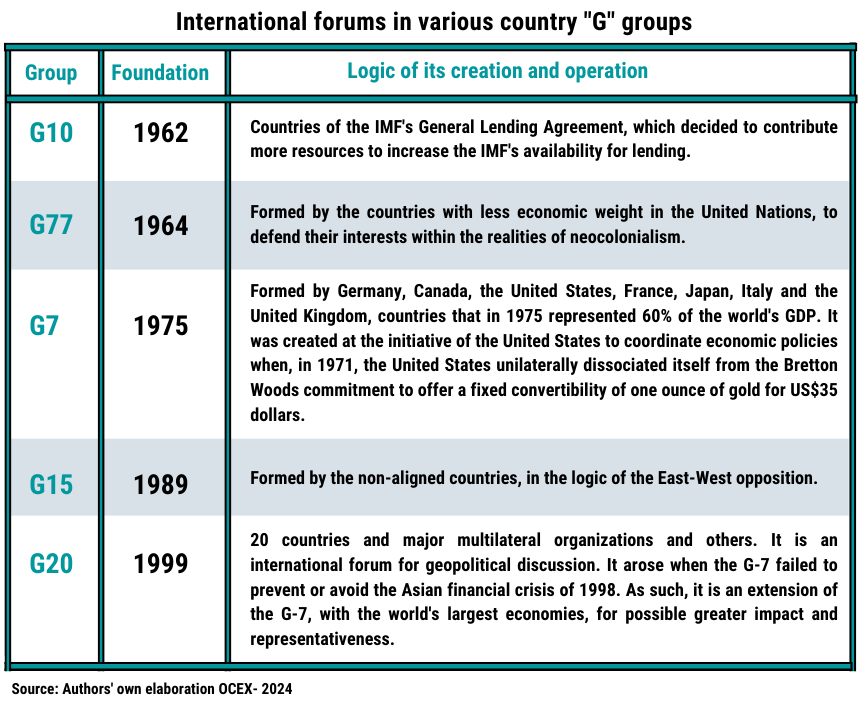

Birth of the G7. The United States understood that to avoid this there was a need to establish permanent forums for financial, economic and political coordination between the most important industrial and commercial powers. Thus, in 1975, the G7 was born. It is not an official, formal entity and therefore lacks the authority to enforce the plans it discusses or the policies it recommends. It is, rather, an intergovernmental political and economic association and setting, made up of the countries accredited as the largest developed economies in the world and, as such, the decisive nations in world trade, which at the time were: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada. The leaders of the governments of these countries meet periodically to discuss economic and monetary issues, since their main objective is to act in concert to address global problems, especially economic matters. The resolutions adopted by the G7, at the end of each meeting, are not binding, but merely indicative. Its ultimate purpose is to design a joint action plan with which to respond to the challenges. Since its creation, the G7 has addressed and reached agreements on financial crises, monetary problems and critical trade issues, such as the oil supply crisis.

policies it recommends. It is, rather, an intergovernmental political and economic association and setting, made up of the countries accredited as the largest developed economies in the world and, as such, the decisive nations in world trade, which at the time were: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada. The leaders of the governments of these countries meet periodically to discuss economic and monetary issues, since their main objective is to act in concert to address global problems, especially economic matters. The resolutions adopted by the G7, at the end of each meeting, are not binding, but merely indicative. Its ultimate purpose is to design a joint action plan with which to respond to the challenges. Since its creation, the G7 has addressed and reached agreements on financial crises, monetary problems and critical trade issues, such as the oil supply crisis.

The anachronism of the G7. At the end of 2001, Jim O'Neill, one of the most important analysts at Golden Sachs, wrote a report in which he tried to demonstrate that the G7 composition was no longer a forum in which truly meaningful coordination of the world economic policy could be really achieved (O'Neill, 2001). His argument was that while some of the countries that make up the G7 did not really have global weight, such as Italy or Canada, other countries, which are not part of the G7, had acquired greater weight, meanwhile, and should be part of economic governance. central world. O'Neill argued that the countries that made up the G7 had been left with an anachronistic weight. Therefore, the world forum they formed was no longer the appropriate expression of the relative weight of nations and, as such, had lost its ability to confront global problems.

Hence he proposed a reform of the G7. He made a metaphor, he said that the G7 wall had to be put with better bricks than the ones it has. His article was called: Building Better Global Economic BRICs. This title was a play on words. He used the pronunciation of the English word bricks (Brics), which means bricks, but in that onomatopoeia he introduced, at the same time, a suggestion: that pronunciation (BRIC) is also the acronym that is derived from the countries Brazil, Russia, India and China.

BRIC - A first attempt at geopolitical rapprochement.The functional analysis. O’Neill’s G7 reform proposal was merely functional. He showed that the impacts of the monetary, economic and trade policies of Brazil, Russia, India and China had much more weight, in the global economy, than those of Italy and Canada, to take, as an example, two member countries of the G7. For this reason, O'Neill wrote, the economy of the world would work better “If the G7 became a forum in which true coordination of global economic policy was debated” (op.cit).

Of course, O'Neill's proposal was never taken into consideration, because the G7 is a geopolitical grouping, not just an economic one. However, his analysis continued to make noise among analysts. In 2003, Dominic Wilson y Roopa Purushothaman, also of Golden Sachs, following O'Neill's reasoning, published an analysis entitled “Dreaming of the BRICs: The course towards 2050”. In that analysis they confirmed O'Neill's forecasts and carried them forward. Conclusions that they themselves presented as truly dramatic: in 2024, they said, the BRICs would represent 50% of the economic weight of the entire G7. In 2039, they would surpass it. And yet, the G7, the club of the West and the hegemonic dominance of the United States, would continue to exclude what would be the largest segment of the world economy. They were showing the critical development of a geopolitical contradiction that had to be faced.

The continuity of an idea that tend to self-enforcing itself. In their article, Wilson and Purushothaman said that the expected results were impressive. Brazil, Russia, India and China - the BRIC economies at the time - were on their way to becoming the largest force in the world economy, within the next 50 years. They said that within 30 years, in the G7, only the United States and Japan would be major economic forces. And yet, they questioned that nothing pointed to a change in the composition of the G7, which made it openly exclusive and low-functional. Since then, academic analyzes confirming these Goldman Sachs reports have multiplied. We have to say that several years passed without anything happening.

A first attempt at a geopolitical approach. From economic analysis to geopolitics. On September 20, 2006, Vladimir Putin invited the foreign ministers of China, India and Brazil to meet informally, taking advantage of the presence of the three in New York, on the occasion of the 61st General Assembly of the United Nations. The spokesperson for the meeting was, of course, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. There he shared with the press that Putin had conceived the need to find some way to institutionalize the collaboration of those four countries. International economic events would reinforce that initiative. The following year, in 2007, China's GDP surpassed that of Germany. In 2008, Brazil, China and the oil countries established a common sovereign fund, as a vehicle to invest excess capital.

The global economic crisis accelerates the processes. The 2008 financial crisis meant a real boom for large emerging countries. At the lowest point of the crisis, in 2009, India achieved the highest growth rate in its history, almost 10%. At that time, the conditions were ripe to assume a collective line of international politics. On June 16, 2009, Brazil, India and China responded confidently to a Russia's call in Yekaterinburg to create a new world forum: the BRIC.

The following year, South Africa joined, adding, in 2010, the letter “S” to the acronym, which became BRICS. With the incorporation of South Africa, the BRICS cover 30% of the planet's territory and 42% of the world's population. In 2023, the BRICS accounted for more than 23% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP) and 18% of international trade. (Takushi, 2023) emphasizes the speed and amazingness of the rise of the BRICS countries: “The rise of China-Russia-India-Brazil-South Africa is absolutely amazing. In 2000, these five BRICS nations barely represented 18% of world GDP, compared to 47% for the G7, that year. This year, the BRICS reached 32.1% of world GDP, compared to 31.4% of the G7 (PPA).”

At their very birth, these countries appear to be contentious and vindictive (Radulescua, 2014). There they warned, for the first time since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the internatio nal need to build, "a more democratic and just multipolar world order, based on the international rule of law, equality, mutual respect, cooperation, action coordinated and collective decision-making where the interests of all States will truly be taken into account" (Declaración de Ekaterinburgo, 2009).

nal need to build, "a more democratic and just multipolar world order, based on the international rule of law, equality, mutual respect, cooperation, action coordinated and collective decision-making where the interests of all States will truly be taken into account" (Declaración de Ekaterinburgo, 2009).

The weight of China's geopolitical leadership. Those are the BRICS countries. Thus their international coordination was born. But, although the first step of the initiative, in itself, was the product of the urge of the Russian political leadership, the decisive weight of its processes has been determined by China's leadership, which has been at pains to offer a horizontal rather than vertical type of leadership.

Long before the BRICS, since the beginning of the century and even before its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), China had been understanding the need to eventually counteract the arbitrary weight exercised by the G7 and how this would only be possible through South-South collaboration and all the way through the strengthening of the economic capacities of the countries of the Global South. China acted first in Central Asia, with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, created at the initiative of China in 2001, where Russia was also present. Next was the China-Africa Forum, also known as FOCA. Therefore, when the Russian initiative for the formation of the BRICs appeared, China joined in and enthusiastically embraced it and quickly took the lead. In 2012, the Belt and Road Initiative, also known as the New Silk Road, was launched, focused on cooperation, financing and infrastructure development. In that same sense, the immense network of development banks in China was created, which includes the China Development Bank, the China-Africa Development Bank, the China Construction Bank; the Export-Import Bank of China and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The New BRICS Development Bank and the Contingency Reserve Agreement are added to this financial network.

At some point, before the beginning of the century, China began to discuss in different forums what was called the Beijing Consensus, as a development model in contrast to the neoliberalism of the Washington Consensus (Fanjul, 2009). Thus, due to its commercial weight, the success of its economic policies and the increasing clarity of its positions within the BRICS, aimed at the creation of a multipolar international order, it can be said that China is the leading political, ideological and economic force in the BRICS forum. (Yağci, 2016).

The concept of the Global South. The BRICS have come to give an organic and geopolitical expression to all the countries that are included in the concept of the Global South. This refers us to a conceptualization of countries that is gaining more and more notoriety in the world. It is a set of countries that are geographically and culturally heterogeneous, but that share common historical, political and economic elements (Jiagui, 2020). The concept of the Global South identifies countries that historically suffered colonization processes, do not really have defining weight in international politics and aspire to economic growth that allows them to increase their participation in the distribution of the world's wealth.

It is an emerging geopolitical reality (Pelfini, 2015) that is linked to old contrasting concepts, used by the social sciences and also by politics, such as: center/periphery; North/South; East/West; development/underdevelopment. This reference even includes developed/underdeveloped (or, euphemistically, “developing”) countries. There are also references to the geopolitical alignments of the Cold War era, such as aligned/non-aligned countries.

What is new about its understanding as the Global South is its reference to a world that, while globalized, is also segmented between the countries that benefit most from globalization and the countries that feel that their participation in the world system leaves them behind in human development and social well-being. It is a collective understanding of demonstrable distributive malaise, which is an expression of a polarized world reality, such as the Global North, in its dominant segment, and the Global South, as the sector of countries with contrasting and aspirational realities, which were previously called “Third World". The BRICS come to offer an alternative and open path and, as such, become vectors with leadership in the Global South (Sahay, 2023).

The following capsule will explain more specifically the birth and evolution of the BRICS, its development since its summits, the current situation and the controversies and perspectives that arise.

References

- Duque, Armando. 2014. De Bretton Woods a la crisis. Universidad Central de Chile. En: https://afese.com/img/revistas/revista56/woods.pdf

- Fanjul, Enrique. 2009. El Consenso de Pekín: ¿un nuevo modelo para los países en desarrollo? ARI Nº 122/2009. Real Instituto Elcano. En: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/145871/ARI122-2009_Fanjul_Consenso_Pekin_paises_desarrollo.pdf

- Haibin, Niu. 2012. Los BRICS en la gobernanza global: ¿una fuerza progresista? - Friedriech Ebert Stiftung (FES). New York. En: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/09592.pdf

- Maihold, Günther y Villamar, Zirahuén. 2016. El G20 y los países emergentes. Foro internacional. Vol.56 no.1 Ciudad de México. México. En: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-013X2016000100165

- Marín Sánchez, Eva. 2011. Una aproximación al papel de las instituciones de Bretton Woods en la actual crisis económica internacional. Tesis de grado. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena. En:https://repositorio.upct.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10317/1909/tfg9.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- O’Neil, Jim. 2001. Building Better Global Economic BRICs. Global Economics Paper No: 66. Golden Sachs. New York. En: https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/archive/building-better.html

- Salama, Pierre. 2014. Las economías emergentes, ¿el hundimiento? Foro Internacional, vol. LIV, núm. 1, México. En: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/599/59940020001.pdf

- Takushi, Christian, 2023. Geopolitical Update: BRICS overtake G7, 29 nations defy the USD and the West. Geopolitical Research Web Site. Suiza. En: https://geopoliticalresearch.com/?p=19385

- Wilson, Dominic y Purushothaman, Roopa. 2003. Dreaming With BRICs: The Path to 2050. Global Economics Paper No: 99. Goldman Sachs. New York. En: https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/archive/archive-pdfs/brics-dream.pdf

- Yağci, Mustafa. 2016. A Beijing Consensus in the Making: The Rise of Chinese Initiatives in the International Political Economy and Implications for Developing Countries. PERCEPTIONS, Journal of International Affairs. Volume XXI, Number 2, pp. 29-56. En: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/815718

- Radulescua, Irina Gabriela, Panait, Mirela, Voicab, Catalin. 2014. BRICS countries challenge to the world economy new trends. Procedia Economics and Finance 8 (2014) 605 – 613. ScienceDirect. En: https://www.academia.edu/19402506/BRICS_Countries_Challenge_to_the_World_Economy_New_Trends?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

- Jiagui, Chen, Xiaoijing, Zhang., 2010. Shared Rapid Economic Growth, BRICS Have Different Development Modes, China Economist, Vol. 5, No.1/2010. En: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1538749

- Sahay, Tim, Mackenzie, Kate (2023). El nuevo orden de los BRICS. Le Grand Continente. En: https://legrandcontinent.eu/es/2023/09/05/el-nuevo-orden-de-los-brics/

- Pelfini, Alejandro y Fulquet, Gastón (coordinadores). 2015- Los BRICS en la construcción de la multipolaridad: ¿reforma o adaptación? CLACSO. Buenos Aires. En: https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/bitstream/CLACSO/14303/1/Interior.pdf